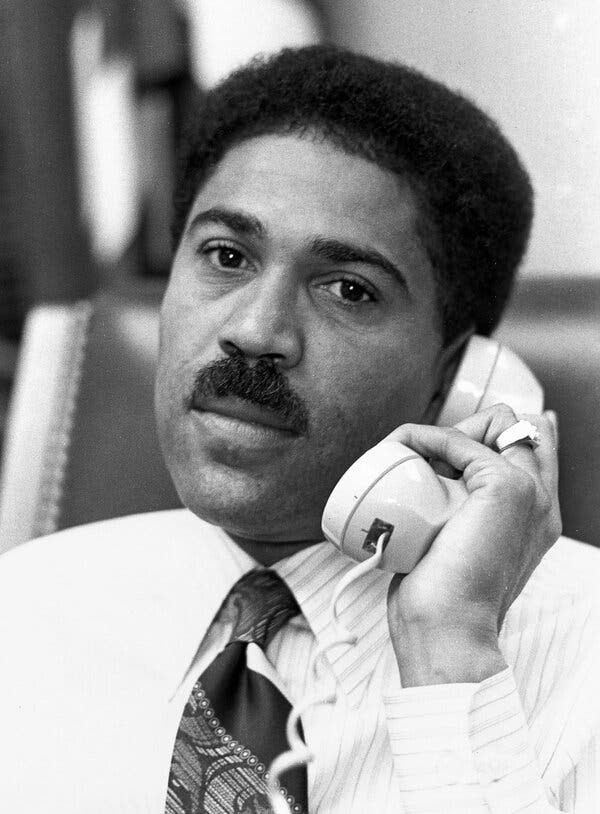

William L. Clay, who became the first African-American elected to the House of Representatives from Missouri, co-founded the Congressional Black Caucus and forcefully promoted the interests of poor people in St. Louis and beyond in his 32 years on Capitol Hill, died on Thursday in Adelphi, Md. He was 94.

His son, William L. Clay Jr., who was elected in 2000 to take his father’s House seat and served until 2021, confirmed the death, at the home of Mr. Clay’s daughter Vicki Jackson. He lived in Silver Spring, Md.

From his election in 1968 until he retired after 16 terms rather than run again in 2000, Mr. Clay had no interest in legislating or lobbying for those who enjoyed prosperity and influence. “I don’t represent all people,”

he said in an interview

with The New York Times during his 1982 campaign. “I represent those who are in need of representation. I have no intention of representing those powerful interests who walk over powerless people.”

An uncompromising liberal Democrat, Mr. Clay was one of 13 founders of the Congressional Black Caucus, organized in early 1971 to concentrate on issues directly affecting Black Americans. At once, he moved to set the caucus on an aggressive course as it boycotted President Richard M. Nixon’s State of the Union address in January 1971.

“We now refuse to be part of your audience,” Mr. Clay wrote to Nixon on behalf of the caucus, whose members were unhappy with the president’s initial reluctance to meet with the group. When Nixon did meet with the caucus that March, each member cited a major concern for Black constituents. Mr. Clay said federal grants were needed to help impoverished Black students repay loans for their education.

Mr. Clay was a persistent critic of the Nixon White House. In 1971, as Nixon insisted that he was “winding down” the war in Southeast Asia, Mr. Clay told Newsweek magazine that it was “pitiful that Black people have to travel 15,000 miles to die for the rights of yellow people that Black people don’t have.”

That same year, he lashed out at Vice President Spiro T. Agnew, who by then had established himself as the administration’s chief baiter of liberals, the news media and others in bad odor with the White House. “In my opinion, our vice president is seriously ill,” Mr. Clay declared after Mr. Agnew had criticized some Black leaders. “He has all the symptoms of an intellectual misfit.”

Representative Gerald R. Ford of Michigan, who was then the House Republican leader (and who would become vice president when Agnew resigned in disgrace in 1973 after pleading no contest to tax evasion), pronounced himself outraged by Mr. Clay’s remarks and said he should apologize.

Mr. Clay did not, saying instead that “Gerald Ford suffers from the same illness Agnew suffers from.”

Mr. Clay’s enmity toward Nixon did not end with Nixon’s death on April 22, 1994. Barely five months later, the Postal Service announced that it would issue a stamp honoring Nixon, in keeping with a longstanding tradition of issuing stamps honoring deceased presidents.

Mr. Clay, who was chairman of the House Post Office and Civil Service Committee, protested that decision in a letter to Postmaster General Marvin T. Runyon. “The logic of honoring this disgraced president escapes me,” Mr. Clay wrote, alluding to Nixon’s 1974 resignation over the Watergate scandal. “He lied to the American people. He lied to the Congress.” The service did issue a 32-cent stamp bearing Nixon’s portrait in 1995.

Mr. Clay had adopted his sometimes pugnacious attitude long before he came to Washington.

William Lacy Clay was born in St. Louis on April 30, 1931, the fourth of seven children of Irving and Luella (Hyatt) Clay. His father was a welder. The family lived in a cold-water apartment. William worked two jobs as he attended Saint Louis University, from which he graduated in 1953 with a degree in political science and history.

Soon after he graduated, he was drafted into the Army. In his two years in uniform, by his account, he got the impression that the Army was unofficially discouraging Black and white soldiers from using the same swimming pools and going to the same barber shops and social clubs. So he dared to remind his superiors that segregation in the military had been outlawed in 1948 under an executive order by President Harry S. Truman.

After his discharge, he returned to St. Louis, where he became a familiar figure in civil rights protests. He spent 112 days in jail in 1963 after he was arrested in a demonstration against the hiring practices of a St. Louis bank.

From 1959 to 1964, Mr. Clay was on the Board of Aldermen, the legislative body for the city of St. Louis. He was active in union affairs, for the union representing city employees and later for a steamfitters local. He held a variety of jobs in real estate and the insurance industry and for a time ran a cocktail lounge called the Glow Worm.

Mr. Clay was elected to Congress from a newly created House district in 1968. “I figure my constituency will stretch from the Mississippi River to about the Rocky Mountains,” he said.

In fact, Mr. Clay did travel throughout the country to take part in civil rights demonstrations. And he was one of several Black congressmen

to demonstrate in 1984

at the South African Embassy in Washington in favor of sanctions against South Africa’s apartheid government. He was arrested and charged with civil disobedience.

Although he easily won re-election time after time, reflecting his popularity with his constituents, Mr. Clay did not have an unblemished record on ethics. In the 1970s, he came under fire for billing the government for car travel when in fact he was traveling by air.

His traveling style resurfaced during the 1982 campaign, when his opponent criticized him for flying first class. “I always ride first class because I’m a first-class person,” Mr. Clay retorted. “Anyone who’s second class shouldn’t even think about running for Congress.”

In addition to his daughter Vicki and his son, William, who is known as Lacy, survivors include another daughter, Michelle Clay; a sister, Flora Everett; five grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren. His wife, Carol Ann (Johnson) Clay, whom he married in 1953,

died

in February.

Speaking at a convention of the A.F.L.-C.I.O. in 1975, Mr. Clay summed up his personal and political philosophy: “If you want equity, justice and equality, you must follow the lead of the civil rights movement, the student movement, the women’s movement. Become irritants, become abrasive. Your political philosophy must be selfish and pragmatic. You must start with the premise that you have no permanent friends, no permanent enemies, just permanent interests.”

David Stout, a reporter and editor for The New York Times for 28 years, died in 2020. Ash Wu contributed reporting.